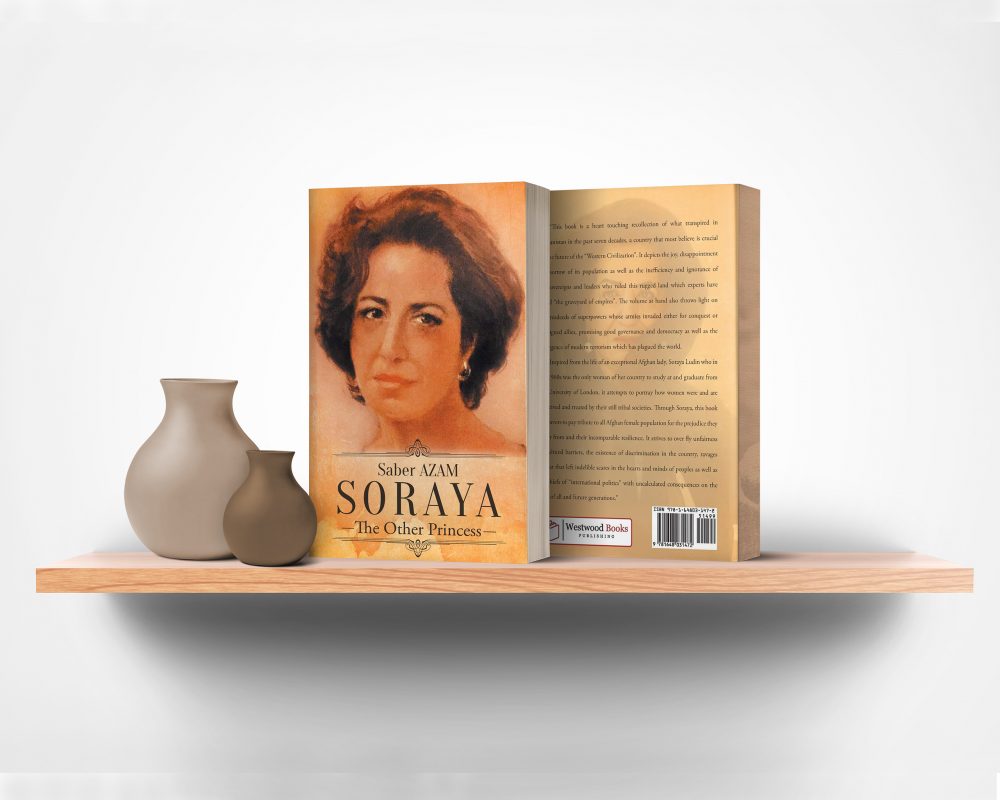

Inspired by the life of Soraya Ludin, a great Afghan lady, this magnificent book will also enthuse other women around the world. Saber Azam expertly describes that what we do in the present time will affect the future and shape our children’s prospects.

Soraya: The Other Princess is also a story about the recent seven decades of Afghanistan history. This country has been oppressed and corrupted primarily by its leaders and the unending rivalries among regional and superpowers. Azam vividly describes that Afghanistan may have fallen deep. Yet, hope still fills the hearts of its inhabitants because of Afghan women who remain optimistic and never give up on dreaming big about their country.

Indeed, Soraya: The Other Princess recounts a very inspiring narrative about the life and tireless efforts of a woman for her shattered country by the ravages of diverse wars.

Learning about the writer will make it even more real, fascinating, and thoughtful. Let us get to know the man behind the incredible story!

It was established principally that your inspirations in this book were the great women in your life, your mother/s. Moreover, we would like to know what made you decide to write about this story? What was your motivation?

In general, every sound person is inspired by her/his parents, particularly the mother/s, and I am of the opinion that each individual’s life can be a remarkable story to write about.

I am privileged for having a very dynamic, meaningful, and colorful life. My experience of grasping the essence of what people believed and how they lived in Afghanistan began at the age of thirteen when we lost our father, and I had to tour half of the country, searching for people who owed him money.

The journey to Europe by road allowed me to meet wonderful and extremely helpful people in Iran, Turkey, Bulgaria, Serbia, Croatia, Austria, Germany, and Switzerland. It coincided with the bloody takeover of Afghanistan by communists and the beginning of the country’s cataclysm. Since then, I rubbed shoulders with scholars, politicians, diplomats, freedom fighters, ordinary people, and more specifically, victims of various tragedies in Asia, Europe, and Africa. In fulfilling my duties, I also met from time to time with those who had inflicted misery to innumerable innocent people, mainly women, and children. Therefore, I decided to share my experience with others by writing about what I went through without censuring the unfitness and idiocies perpetrated by some decision-makers. It requires courage and audacity.

Today, most powerful seem disconnected from the daily realities of those they should care for and protect. For me, there was no better pleasure than to share a few moments with ordinary people who struggled to survive, particularly when uprooted from their dwellings and forced to flee either within their countries or in neighboring lands.

In this book’s particular case, I met Soraya Ludin at the age of twenty and was stunned by her knowledge, honesty, and clarity of thoughts. She belonged to the most upper layer of society. However, she reached everyone in need. It is common to see someone wishing to be rich, detain power, and exercise authority. But, an influential person rarely abandons the privileges to feel poor people’s pains. Soraya Ludin is one of such graceful and gracious persons. And I decided to write a book, inspired by the pages of her life that I know.

You also mentioned that you had the privilege of knowing Soraya Ludin. How did you meet her?

When we lost our father, I started to work beside my national studies to earn some money supporting our large family, and attend an American school to learn English. This allowed me to work with international entities and finally secure a part-time job in the International Trade Center of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, where Soraya joined as the most senior Afghan staff. I worked for over a year and a half under her guidance before being awarded a scholarship by the Swiss Federal government and departure for Lausanne. I speak in detail about our encounter in my book.

Later on, she arrived in Geneva. We were both refugees and began substantial cooperation supporting Afghanistan’s liberation from communism and Soviet claws. She was the engine and the shining star of our struggle in Western countries. Her vision, hard work, analysis of any given situation, and solution-oriented bright mind had no equal to the extent that former Afghan prime ministers and ministers sought her advice on multiple issues. Her courteous courage, pertinence, grasp of complex political problems, and an acute sense of diplomacy were impressive. She is by far a high-class personality that appeared in a country where decision-makers did not appreciate bright people, particularly women. And this has been a significant tragedy in Afghanistan.

Tell us more about Soraya and her captivating personality.

Soraya is a brilliant and humble person. Her distinguished father was her protector, mentor, guide, and friend. Despite his heavy and vital responsibilities, he was always available and had time for her. Honesty, courage, and respect for others’ opinions are in her blood. In her childhood in the 1950s, she learned from the devastating situation of ordinary people in Afghanistan to people of color’s appalling conditions in the United States. In her youth, she began to grasp the fine lines of politics and diplomacy in London. As a mature person, she shined in Afghanistan and became Assistant to one of the country’s most remarkable prime ministers. She learned from the palaces as well as remote and impoverished corners. She met superpower dignitaries and common people with whom she spoke about facts with a solution-oriented spirit.

Her background in philosophy and economics was instrumental in her logical approach. Every word, gesture, and behavior was important for Soraya, and she instantly grasped the micro and macro dimensions of matters she handled. Ministers popped in her office to seek her view on state affairs, and clerks sought her advice on issues related to their daily lives. She was and still is like a magnet!

Soraya Ludin fought injustice with energy and dedication. Her struggle against the communist atrocities and the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan was unique and creative. She is a rock-solid friend to the cause of fairness and equality of rights for people of all races, colors, genders, social backgrounds, and orientations. Her worse enemy is dubiousness, ruses, and mediocracy.

Though I never intend to infringe on her private life, I can say that she is an extraordinary mother and a cherished and caring grandmother.

If Soraya Ludin were a West European or an American citizen, she would have been a prime minister, a minister, or an amazing and efficient Secretary-General of the United Nations. Unfortunately, and as I said earlier, Afghan rulers never valued such open-minded, fair, intelligent, and talented people. I hope that through this book, people will learn about her dazzling personality and endeavors for a genuinely free Afghanistan.

What is your favorite part of this book, and why?

This book means a lot to me. It is about my origin, country, people, and a dear friend. I have said to many that it is the first and will be my last book – I intend to revise it at my old age. Every event, scene, and word is essential. The challenging parts are Soraya’s childhood and youth. I had to imagine and extrapolate her personality as close as possible to the real person. It was the most thought-provoking test, and I had to rewrite parts of those chapters several times or improve repeatedly diverse sections.

Tell us about Afghanistan and how it was like living there, as a child and then now as an adult.

I believe the best time of history in Afghanistan was between 1960 and 1975, particularly the decade of parliamentarian democracy. The country progressed slowly but steadily. Women’s emancipation did not reflect a political agenda designed by the rulers and seemed natural. Education became accessible to a significant number of poor people who lived in remote areas of the country. The elections became a known vocabulary. Though symbolic as most assembly chamber candidates had to receive the power palace’s endorsement, some could still get elected based on their own merits; and their number was growing. Any significant failure of the government ended in the Prime Minister and the cabinet losing their seats.

From a geographic perspective, the highland and lowland of Afghanistan had their specific climatic conditions. There was water in the rivers and countless streams in Kabul and elsewhere in the provinces. The country possessed effective four seasons. Its spring was a reflection of paradise on earth and the season of unique and incomparable mulberries. The summer presented the abundance of juicy and delightful fruits such as apple, pear, apricot, etc. Grape festivity colored the autumn in Afghanistan. And the winter was harsh and merciless. This is how I remember my childhood.

Since 1978, Afghanistan began its slide to a political, social and security cataclysm. Contrary to some Afghans, I believe the forceful change of regime by pro-Soviet officers of the army from the kingdom to an unwanted republic was the source of decades of tragedy in the country. It changed the neutral status of Afghanistan. We then became the puppet of the Soviets, Pakistan, and other regional and international forces.

So far, there is no solution on the horizon, and the tragedy, destruction, and incomprehension will continue. I also write political articles to draw the attention of decision-makers, mainly Americans, on what is needed for durable and sustainable peace in Afghanistan. I hope they adhere sooner to the solution I propose. Only time will tell us.

Besides quality education, what do you think will change Afghanistan and make it a country that will thrive in the future?

The Afghan problem is deeply rooted and cannot be solved with a magic wand. No single actor or power or a combination of isolated interests can succeed. There are very profound internal challenges, regional impediments, and international hurdles. They are interconnected and constitute the core issues to address. Therefore, the solution to the Afghan crisis should address all dimensions at once. Otherwise, it would not be crowned with success.

Afghans must decide what type of society they would like to live in. Nepotism and ethnic biased, practiced by the rulers, have caused enormous harm to the country. Would Afghans accept to consider merit, knowledge, and competence as the criteria for assuming public responsibilities? In addition, unforgivable atrocities have been committed based on ethnic, ideological, and religious considerations in the last four decades in the country. There has been no truth and reconciliation effort undertaken. Some perpetrators are still in power. People live with a strong feeling of revenge in mind. Without sincere acknowledgment of crimes committed and a truthful endeavor to forge a common and safe future, they will remain apart. This brings me to underline that while Afghanistan is a country with defined and internationally recognized boundaries, Afghans never formed a nation. Rulers always played the divide and rule policy, stigmatizing those who did not belong to their “clans.” Afghanistan needs a robust and long-term nation-building plan. The country has been affected by the profound social, political, and economic transformation in the last four decades. And the current constitution of the country did not reflect such alterations. It has to be revised.

The post-Taliban period (2001- present time) in Afghanistan is marred with nepotism, rampant corruption, tribalism, violation of the rule of law by government dignitaries, and many other disgraceful behaviors by the rulers. Good-governance does not seem to exist in the dictionary of Afghan big-wigs. This country’s future would be in jeopardy without a comprehensive and workable anti-corruption mechanism run by honest and incorruptible people. The government does not appear to have short- med- and long-term social, political, and economic development plans for the country. Often it behaves like a cockroach without filiform antennae. The population is unaware of where the governing team will take them tomorrow, a year from now or ten years later. Such visions are needed in a functional governing system. Finally, the integrity of elections must be ensured through robust and principled procedures, professional staff, and an unbiased oversight system to ensure honesty, impartiality, and fairness.

On the regional arena, Afghanistan is the weakest element of a volatile geographic zone. Indo-Pakistan, Saudi Arabia-Iran, Indo-China, and many other tensions directly affect this country. It can no longer afford to be the playground for proxy wars that must end promptly. There is enormous anxiety over water and natural resources attributions and distribution. The region needs to have a clear understanding about such vital issues. Climate change has worsened the situation, particularly in Afghanistan, a producer of water to Iran and Pakistan. Southwest Asia faces numerous claims of independence. The Kashmiri, Baloch, and other minorities’ desire to be independent affects different neighbors’ posture regarding Afghanistan. Pakistan as the protector, trainer, and supplier of the Taliban, has particularly been harmful. This country has to abandon harboring and supporting terrorist groups, and Afghans need to find an amicable solution with all neighbors, but Pakistan, particularly, to ensure peace, security, and prosperity of the region.

On the international arena, Afghanistan is chaperoned by the current political, military, and economic world leader, the United States of America. However, the rise of the People’s Republic of China, the Russian Federation, and India has already placed Afghanistan at the center of what I call “the new great game,” implying arduous competition for the future leadership of the planet. A weak, fractured, and war-torn country would not be able to avoid proxy wars on its territory. Moreover, new emergencies arise requiring funding. Therefore, Afghanistan is no longer a priority, and the West has become tired of breastfeeding and babysitting a country run by corrupt and incompetent leadership. Finally, and unfortunately, because of the modern form of terrorism, Islam’s image has been tarnished significantly. Pakistan and Afghanistan under the Taliban regime played a substantial role in this sad development by harboring, protecting, and arming Al-Qaeda and Osama Bin Laden. Even now, the Taliban, their Islamic State associates, and other terrorist groups commit heinous crimes against humanity in the name of a religion that promotes mercy, generosity, peace, and prosperity for all. Afghan decision-makers must undertake an enormous effort to dissociate themselves from harsh Islamic trends of thought.

As you can see, the national, regional, and international challenges are colossal, and addressing them requires honest, competent, and visionary leaders in Afghanistan. This is not at all the case currently! Therefore, what I wish for Afghanistan, and I hope the Biden administration will hear me, is a new generation of young, able, and incorruptible leaders in this country to take charge for a transitional period of 5 to 7 years. During this period, the team should address the challenges mentioned above, lead a durable and sustainable peace process, prepare and conduct transparent and honest elections, and hand-over the country to the rightful winners. To ensure that such a strategy achieves its objectives, I think none of the transition government leaders should assume future public functions. They can form a council of ethics and good-governance, act as role models, and denounce any wrong-doing that will happen in the future.

What do you hope for in Afghanistan?

I hope for Afghanistan what people in every corner of the world deserve, i.e., peace, serenity, prosperity, and trust in the future

Afghans cannot bear further the heavy burden of eternal wars in the name of whatsoever doctrine. There should be an end to the cycles of violence. They must regain control of their faith, a tolerant, merciful, helpful, and peaceful Islam that would allow, like in the old days, believers of other religions to live side by side, working together to develop the country. They must reject and expel extremists. Like my Hindu, Jewish, and Sikh countrymen and women, I have beautiful memories of a country that was a model of tolerance. My best friends were Jacob and Jugal. Gayan Singh and Jaman Singh were our uncles who regularly came home and brought us “laddu,” Indian sweets, particularly during the Diwali festival. We were greeted with open arms in synagogue and mandir. It would not be easy to return to the past. All Afghan Jews left the country, and not many Hindus and Sikhs remain in Afghanistan. But, Afghans can and must inspire from their not distant past to forge a much better future.

We know you began writing after retiring from your United Nations duties. What feeling does it give you to write?

I believe writing is like composing music. A writer melts into the book’s characters and is part of the locations, edifices, geographies, seasons, and many other details that she or he writes about, like a musician who dissolves in a symphony.

Writing gives me an incredibly peaceful feeling. As mentioned earlier, I had an enriching life and extraordinary professions. I love to share with current and future generations my experience and speak candidly about facts that I have observed. Of course, objectivity is relative, but honesty is lifelike. When I finish a political article or a book, there is a breeze of tranquility in my mind. I am not yet a renowned writer – but it is not a concern. I defend human values and have the courage to call a spade a spade. It is my firm belief that sooner or later, people will realize and appreciate my writings.

Have you written other books aside from this one?

Yes, I have. Hell’s Mouth is my second book. It depicts the devastating consequences of the First Liberian Civil War and the extraordinary endeavors of humanitarian workers to support refugees in the neighboring Côte d’Ivoire. I am already busy with the third that will focus on the problem of South Sudan in particular.

Tell us about yourself and your future projects.

I am born in Afghanistan and came to Switzerland at the age of 22 to study at the Lausanne Federal Institute of Technology. It coincided with the takeover of the country by communists. Systematic killings of innocent women, men, and children, violation of human rights, and the imposition of an ideology that the people did not want, and later on the invasion of Afghanistan by the Red Army made me a natural campaigner against the brutality of Soviet policies and strategy in this country. In addition to my academic endeavors, I presided voluntarily for twelve years the Afghan Humanitarian Committee in Geneva. In this capacity, I dealt with politicians, diplomats, humanitarian workers, and Afghan Mujahidin chieftains. After graduation, I worked in the mechanical and medical engineering fields before embarking on a Ph.D. in advanced nuclear technology. The desire to help victims of conflicts pushed me to advocate in Switzerland for the private sector’s commitment to reconstruct war-torn countries. Finally, I joined the United Nations. For nearly twenty-four years, I assumed with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the United Nations Department of Peace Keeping Operations (UN-DPKO) key functions in conflict-affected areas of the world. My background and experience in Afghanistan and efforts to lead rescue operations with the United Nations constitute my writings’ framework and nourishment.

So far, I have self-published and hope to secure the cooperation of a reliable publishing company soon. Fame and gain are not my purposes in life. I defend causes for the well-being of humanity and express matters of concern bluntly. We are in a moment of history when only honesty with our past, present, and future, acknowledging mistakes, sincere desire to repair our misdemeanors, and an ambition to make the planet as much as possible peaceful, pleasant, and promising for all can save us from looming calamities.

I am of Afghan origin and know the people, their painful history, cultural values, Afghanistan’s geography, and its current and future geostrategic position. I have the plan for two or three more books concerning this country.

However, and for global affairs, I have created a character, Abraham, who leads rescue operations in conflict-affected areas of the world. He does not bow to any government, institution, or personality and stands firm in defense of human values and rights. He denounces at the risk of his life misdeeds no matter who commits them, offers solutions to victims of tragedies, and applies the notion of “management with a human approach.” He is in some way a “humanitarian James Bond” and supported by his beloved Selina.

In the exercise of their duties in different corners of the planet, they observe the devastating effects of slavery, colonialism, new colonialism, and offense to the environment. They denounce them with energy and advocate for a new approach by the leaders of most powerful countries to acknowledge the mistakes committed, take corrective measures for them not to happen again, and engage in healing and repairing the pains inflicted to generations of human beings because they had a different skin color, faith, appearance, or political opinion. They must also solemnly engage in saving the planet earth from destruction and address climate change boldly.

I have the framework for several books on Abraham and Selina’s missions. Their next assignment (my third book) will be in Kakuma, situated in the north-western part of Kenya, close to Ethiopia, Uganda, and South Sudan. They will then move to the Balkans or south-east Europe, back to Côte d’Ivoire, divided by a conflict, Bangladesh, Central Asia, and Rwanda.

In a sentence, I hope to be a strong voice for the voiceless! Human values and rights are our most priceless assets; no power, be it political, military, or economic, should be allowed to suppress them.

We have read your political articles too. Your style is forthright, and some may consider it “abrasive.” Do you not fear for your life?

I am not a native English speaker, and, of course, there are certain lapses in what I draft. However, I would not use the word “abrasive”; forthright is the correct term. In my book Soraya: The Other Princess, I quote Ambassador Kabir Ludin, a great Afghan statesman, politician, and diplomat, saying to his daughter Soraya “life and death are in the hands of Almighty God. The certitude of life is death; the timing is the only uncertainty.” Therefore, if we are afraid, the world will not progress. All of us must have the courage for the right reasons because those who inflict misery on others are daring enough to succeed in their unlawful acts. However, I am also conscious of not taking useless risks.

Times change, and with them, the writing styles, diplomacy, politics, and even human behaviors alter. I firmly believe that forthrightness about what has happened in the past is a much more efficient strategy to secure us a better future!

This book is available on Amazon.

Buy your own copy now!